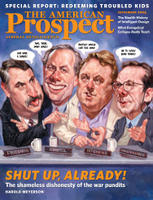

Their War, Too

Are mere pundits responsible when an administration’s policy goes wrong? When their sophistic arguments helped sell and sustain it, very.

By Harold Meyerson

Issue Date: 09.10.05

In the information age, wars are not made by governments alone. This is especially true of wars of choice. When America has been attacked -- at Pearl Harbor, or as on September 11 -- the government needed merely to tell the people that it was our duty to respond, and the people rightly conferred their authority. But a war of choice is a different matter entirely. In that circumstance, the people will ask why. The people will need to be convinced that their sons and daughters and husbands and wives should go halfway around the world to fight a nemesis that they didn’t really know was a nemesis.

That’s why a war of choice is different. A war like the Iraq War, whose public support before the idea was seriously discussed started out well below 50 percent, needs to be sold -- “marketed,” as White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card once put it -- needs, well, marketers.

And, in the information age, an administration can’t, and doesn’t, market alone. It takes an army of salespeople -- it takes a village, you might say -- to accentuate the positive. And when an administration spreads demonstrable lies and falsehoods, or offers “evidence” that can’t be wholly refuted but for which there is nevertheless no existing proof, it takes that same army to stand up and say: “Yes! These assertions are true! Those who deny them are unpatriotic, or simpletons, or both!” And finally, when the war goes terribly, terribly wrong, that same army is called to the ramparts one last time, to say, in a fashion that approaches Soviet-style devotion: “Things are in fact going well! The insurgency is dying! Abu Ghraib is not a scandal! Saddam Hussein did have ties to al-Qaeda; you just don’t know it yet!” And so on.

For its war in Iraq, the Bush administration relied on and benefited from the cheerleading of a group of pundits and public intellectuals who, at every crucial moment, subordinated the facts on the ground to their own ideological preferences and those of their allies within the administration. They refused to hold the administration’s conduct of the war and the occupation to the ideals that they themselves professed, or simply to the standard of common sense. They abdicated their responsibilities as political intellectuals -- and, more elementally, as reliable empiricists.

http://tinyurl.com/d7kt5

*

Are mere pundits responsible when an administration’s policy goes wrong? When their sophistic arguments helped sell and sustain it, very.

By Harold Meyerson

Issue Date: 09.10.05

In the information age, wars are not made by governments alone. This is especially true of wars of choice. When America has been attacked -- at Pearl Harbor, or as on September 11 -- the government needed merely to tell the people that it was our duty to respond, and the people rightly conferred their authority. But a war of choice is a different matter entirely. In that circumstance, the people will ask why. The people will need to be convinced that their sons and daughters and husbands and wives should go halfway around the world to fight a nemesis that they didn’t really know was a nemesis.

That’s why a war of choice is different. A war like the Iraq War, whose public support before the idea was seriously discussed started out well below 50 percent, needs to be sold -- “marketed,” as White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card once put it -- needs, well, marketers.

And, in the information age, an administration can’t, and doesn’t, market alone. It takes an army of salespeople -- it takes a village, you might say -- to accentuate the positive. And when an administration spreads demonstrable lies and falsehoods, or offers “evidence” that can’t be wholly refuted but for which there is nevertheless no existing proof, it takes that same army to stand up and say: “Yes! These assertions are true! Those who deny them are unpatriotic, or simpletons, or both!” And finally, when the war goes terribly, terribly wrong, that same army is called to the ramparts one last time, to say, in a fashion that approaches Soviet-style devotion: “Things are in fact going well! The insurgency is dying! Abu Ghraib is not a scandal! Saddam Hussein did have ties to al-Qaeda; you just don’t know it yet!” And so on.

For its war in Iraq, the Bush administration relied on and benefited from the cheerleading of a group of pundits and public intellectuals who, at every crucial moment, subordinated the facts on the ground to their own ideological preferences and those of their allies within the administration. They refused to hold the administration’s conduct of the war and the occupation to the ideals that they themselves professed, or simply to the standard of common sense. They abdicated their responsibilities as political intellectuals -- and, more elementally, as reliable empiricists.

http://tinyurl.com/d7kt5

*

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home